Herald of a Restless World: first excerpt

Only one month until my biography of Bergson hits the shelves!

Dear friends,

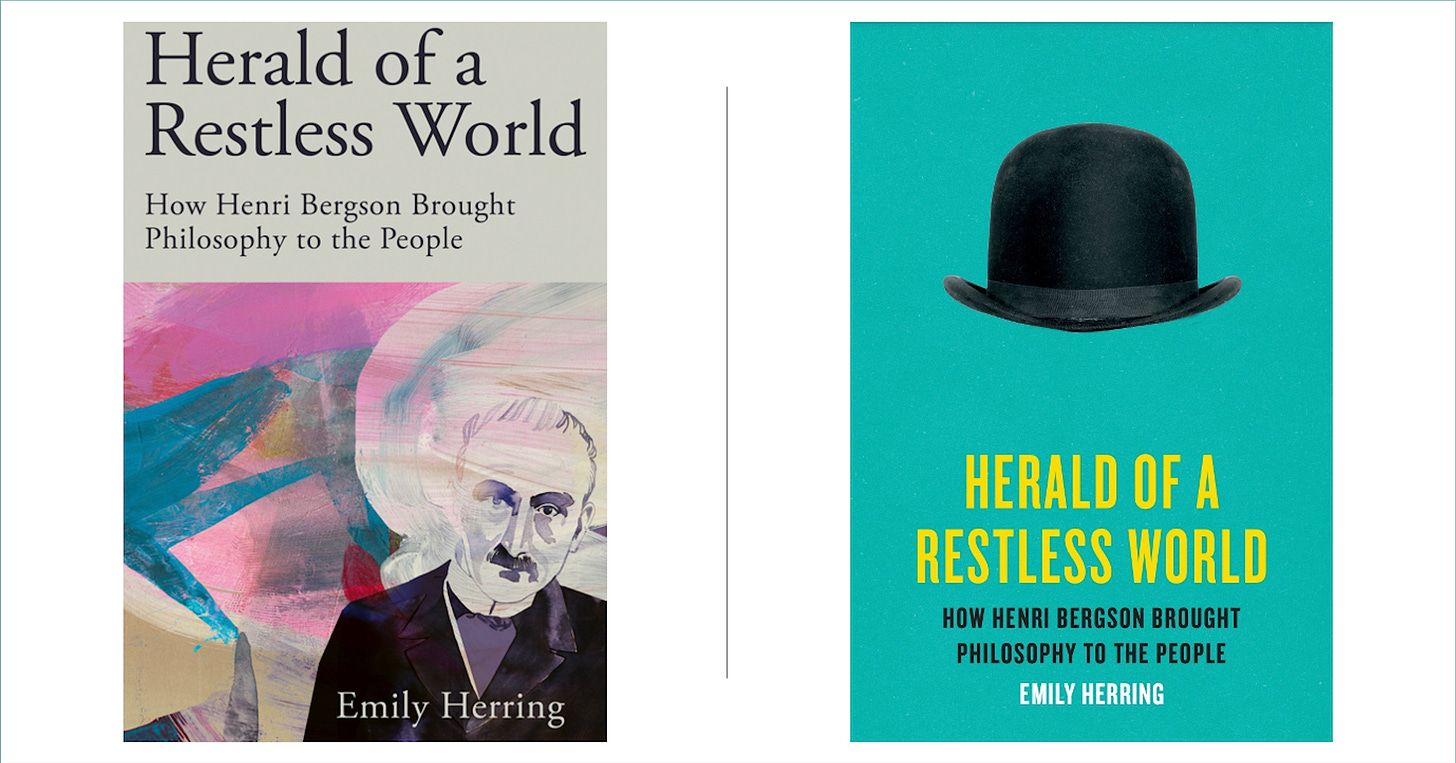

My book, Herald of a Restless World. How Henri Bergson Brought Philosophy to the People, will be out in just under one month!

There have already been two very nice reviews: Kirkus Reviews call the book “A solidly researched and earnestly accessible portrait of a creative, free-thinking intellect” and Publishers Weekly describe it as a “scintillating debut […] [w]ritten in graceful prose and drawing a clear analogy with contemporary techno-optimism and its discontents, this captivates.”

I am beyond excited to share Bergson’s story with you! In that spirit, in the weeks leading up to publication day, I will be sending you a few excerpts from the book. Today I give you the final few pages of the introduction in which I touch upon the unique challenges that come with writing a biography of Bergson, my own personal path to his philosophy, and what I think the book is (not entirely an introduction to Bergson, not entirely an intellectual biography, but another secret third thing).

UN-BERGSONIAN

Writing a biography is a highly un-Bergsonian exercise. The biographer usually unravels the story of a human life from birth to death. She might give her reader the impression that her subject’s life is developing before their very eyes, but in reality she already holds together all the events from start to finish. She looks at portions of a lived experience from the outside, moves them around, and cuts them up into interchangeable pieces. Anyone who is familiar with Bergson’s philosophy knows that such a process is at odds with his description of the flow of time as gradually ripening a person’s existence from within.

Perhaps the only thing more un-Bergsonian than writing a biography is writing a biography of Henri Bergson. On several occasions, including in the will he started drafting half a decade before he died, the philosopher demanded that he be remembered for his philosophy and nothing else: “I have always asked that my personal life be ignored, and that only my work should be examined. I have invariably maintained that the life of a philosopher sheds no light on his doctrine and is of no concern to the public.” He knew that after he died any traces of himself he left behind would be picked apart, that all manner of tributes (which he viewed as unwarranted) would be paid, and that all sorts of erroneous assumptions and preconceptions about his character and intentions would become set in stone. He knew that the wishes he stated in his testament would not be fully respected, and so, before he died, he made sure to quell all future attempts to study Bergson the man, beyond the work. He instructed his wife Louise, who had shared his life for over four decades, to destroy anything he left unpublished after leaving this world. Correspondence, miscellaneous papers, lecture notes, drafts of new ideas — Louise threw it all in the fire. A biographer’s nightmare.

Bergson often repeated that nothing can be learned about a philosopher’s ideas by studying their life. But what if it is precisely their life we are interested in?

MY BERGSON

At eighteen, I used the little I knew about Bergson’s philosophy in my baccalaureate philosophy exam. We were given four hours to write an essay on a single question: “Does language betray our thoughts?” So much of what I then knew of Bergson’s thought felt entirely beyond my reach, but his ideas about language resonated. Words, Bergson said, are mere labels we affix to things. We use concepts to tidy up the overwhelming diversity of reality into neat boxes. But in doing so, we often lose sight of what is special and particular about the different aspects of reality that our words describe, including our own inner lives. Beneath this monochromatic conceptual veil, our vibrant, unique self remains hidden out of reach, unless we know how to look for it. Bergson had implanted in me the idea that philosophy could serve as a window into the world beyond what is given.

At the Sorbonne, I majored in philosophy. In an ocean of Western classics, Bergson’s name bobbed up once in a while alongside Plato, Descartes, and Kant, but I wanted to find out more. Towards the end of my third year, I decided to read his works on my own time, in chronological order. I was met with difficult but beautiful texts that delved into scientific debates for which I had little context. Like so many of his contemporaries, I found that his book Creative Evolution was the one that stood out to me. I was so fascinated by this early twentieth-century philosophical interpretation of biological evolution that I applied to do a master’s degree in the history of science to better understand what was at stake. My curiosity got the better of me, and I ended up writing a PhD thesis at the University of Leeds on the reception of Bergsonian evolution among the biologists of his day. It was only then that I started learning about Bergson’s life, beyond his theories, the life the philosopher himself did not want anyone to study.

I was captivated. Parts of his story read like an adventure novel. Other parts reminded me of the most deranged aspects of our current celebrity culture. As I unravelled the various threads of my research, I realised that there was almost no area of early twentieth-century culture that this soft-spoken, bald-headed French philosopher had not touched. For a time he had been the most talked-about person on the planet, but as I would learn, his name meant very little to most of the academics I encountered in the anglophone world. It has always seemed unbelievable to me that such an extraordinary figure and his incredible story could have been almost entirely forgotten.

This book is not an introduction to Bergson’s philosophy. There have been many of those, hundreds even. The ones I have found the most helpful throughout my studies and research are listed in the “Beginner’s Guide to Bergson” at the end of the book. But naturally, over the course of this book I introduce many of Bergson’s key ideas, as they constitute pivotal “moments” in the philosopher’s journey. This book is not strictly what one might call an “intellectual biography” either. I do not purport to find within the events of Bergson’s life the germs of his ideas. As the philosopher Gabriel Marcel wrote about Bergson: “Did he not teach us how important it is to be wary of a posteriori reconstructions that so profoundly alter the creative process they claim to describe?”

Instead, I like to think of this book as the product of three intertwined and inseparable portraits. A portrait of a man, with aspirations and contradictions. A portrait of his philosophy, which, in various ways, changed the world around him. And a portrait of the world in which the man and his ideas evolved. A portrait is, by nature, a point of view taken on a subject. My own interests, idiosyncrasies, and blind spots will therefore be reflected in my depiction of Bergson’s life, times, and philosophy. But it is my hope that this book will highlight just how profound, interesting, and important Bergson was and why he deserves to be remembered.

It would be a mistake to dismiss Bergson as a mere historical curiosity. In the early years of the twentieth century, his defining of life and consciousness in terms of freedom and creativity reassured those who worried that new discoveries in biology had reduced human existence to a cold mechanical process. His critique of the static symbolism of science resonated deeply with those who had grown suspicious of what they viewed as the excesses of rationality and technology.

New facial recognition and artificial intelligence technologies have us fearing for our freedom and humanity. With the current climate crisis, the survival of our species depends on our ability to come up with creative solutions to unprecedented challenges. Who better to turn to than the thinker of radical change and creativity?

You have just read an excerpt from my forthcoming biography of Bergson, Herald of a Restless World: How Henri Bergson Brought Philosophy to the People (2024 Basic Books).

You will find pre-order links for the book here.

Pre-orders are incredibly important for first-time authors like me because they help build anticipation, boost visibility, create early sales momentum, and garner support from booksellers. Your encouragement is therefore much appreciated!

Thank you so much for reading and I hope you have a creative week!

Emily