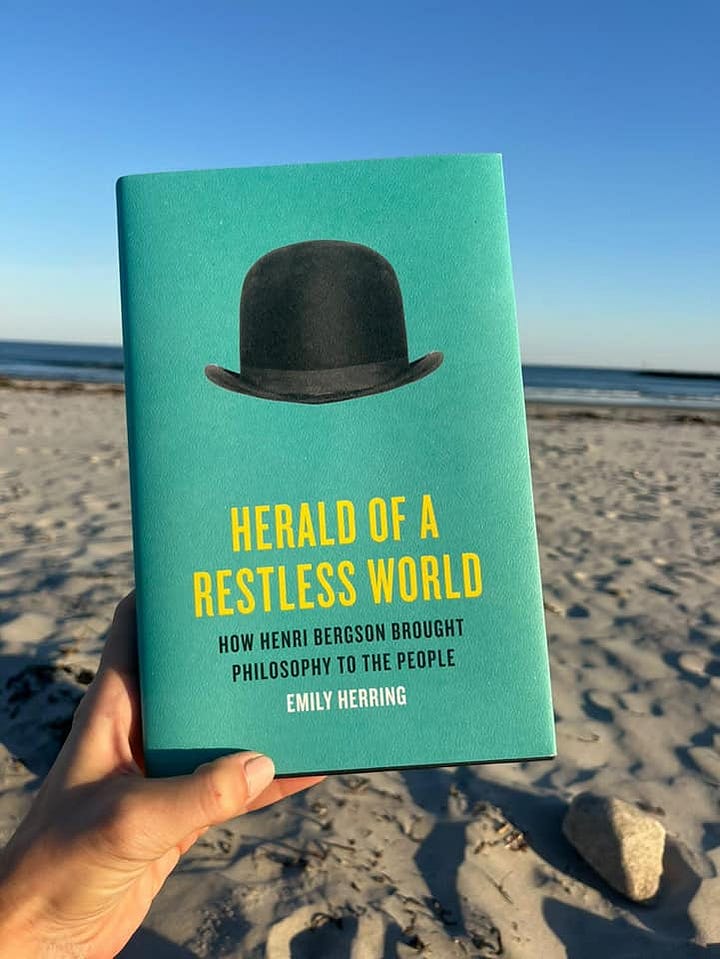

Herald of a Restless World out now!!!

The first biography of Henri Bergson in English is available everywhere you get your books!

Dear friends,

I am delighted to announce that my first book, Herald of a Restless World. How Henri Bergson Brought Philosophy to the People, is now available everywhere you get your books!!! Below I share some thoughts about why I hope my book will inspire a Bergson revival!

It is hard to imagine nowadays that Henri Bergson was once one of the most famous intellectual figures in the world, discussed in philosophical, literary, religious, political and scientific communities. His lectures at the Collège de France in the early 20th century were so crowded that people often had to resort to climbing up the side of the building of the prestigious Parisian institution, and a conference he gave, in French, at Columbia University in 1913 caused the first ever traffic jam on Broadway. Around this time, the philosopher’s influence was so great that the New York Times labelled him “the most dangerous man in the world.”

And yet, despite this intense period of fame, Bergson is perhaps today best known, in the English-speaking world at least, for his brief appearance in a Monty Python sketch. A cheesy game show host (John Cleese) asks an old lady contestant (Terry Jones) a ludicrously challenging question about the history of philosophy. Against all odds, the woman answers correctly (“Is it Henri Bergson?”), before delivering the punch line: “That was lucky! I never even heard of him!” In 1970, the Pythons could safely assume that Bergson’s name would come across as particularly obscure to an anglophone audience, and this is still true today.

But Bergson is more than just the punchline of a joke about obscure thinkers of the past. His life story reads like a Hollywood script in which a greedy producer has tried to cram in too many celebrity cameos. When Bergson was married in 1891, Marcel Proust was his best man. In 1917, the French government sent him on a secret mission to convince US president Woodrow Wilson to enter the war. In the early 1920s, he was involved in a very public debate with Albert Einstein on the nature of time.

It would be a mistake to dismiss Bergson as a historical curiosity. In the early 20th century his philosophy of durée inspired a generation of readers to embrace their own freedom and creativity. At the time, artists, intellectuals, and even scientists were voicing increasingly loud concerns about what they viewed as the excesses of technology and science. They saw the mechanisation of human life as ridding the world of wonder, beauty, and mystery. Many of Bergson’s followers, who felt as though all sense of purpose and moral bearings was being lost, found in his philosophy a much-needed antidote to the disenchantment of the world.

As I researched the life and times of Henri Bergson, I was surprised to find just how much the concerns of his contemporaries echo many of our current anxieties. Quantification is seeping into the most intimate realms of our psyches via algorithms that purport to anticipate our desires in a consumerist, capitalist society. Some engineers believe that they are able to replicate human consciousness through machines, while critics point out that current so-called artificial intelligence programs simply rehash pre-existing materials without ever displaying the creativity and freedom inherent in the human experience.

In his final book, The Two Sources of Morality and Religion, Bergson wrote about the need to inject more spirit— meaning more humanity— into our technology, which is progressing too fast for our ethics to keep up. He also wrote about our need to find ways to open up societies that close up on themselves and retreat into increasing authoritarianism and xenophobia.

I hope readers of Herald of a Restless World will feel, as I do, that Bergson still has a lot to say to the present moment.

There have already been two very nice reviews of Herald of a Restless World: Kirkus Reviews call the book “A solidly researched and earnestly accessible portrait of a creative, free-thinking intellect” and Publishers Weekly describe it as a “scintillating debut […] [w]ritten in graceful prose and drawing a clear analogy with contemporary techno-optimism and its discontents, this captivates.”

Here are more nice things people have said about the book:

Thank you friends for all your support, I leave you with one of my favourite quotes about Bergson from George Tyrrell in 1908: “[Bergson] frankly admits that we must stand on our heads, and seize that brief moment of unstable equilibrium to snatch a hasty glance at things as they really are. We must use our minds in a wholly unaccustomed way, and recognise that its customary use is fatal to speculative truth just in the measure that it is adapted to practical ends. In short, we have to approach philosophy with a new mind and a new method.”

Creatively yours,

Emily

In a belated reply to those, with the rigidly orthodox and righteous mindset similar to Dr.Borumand (...and to poorly paraphrase Deleuze.)

Throughout history, the world of the inquisitively complex can be viewed as a portrait galley. You wouldn't enter an art gallery filled with portraiture through the ages and shout out aloud... these are 'misconceptions' of what a person really is. Every theorem, philosophical proposition or sweeping thesis is an expression of what is means to be human. Captured immutably within their creators own brief and fragile existence. Just as Dr.Boruman's dogmatic ideas on the true nature of reality will pass into obscurity within a few fleeting decades. Mr.Bergson's ideas portray a sublimely creative and nuanced portrait or mirror into ourselves. Housed within the grand gallery of complex personalities that have all asked... who am I?

Bergson’s views was best described as ‘vague nebulosity’! The very concept of ‘Elan Vital’ sums up his misconception of the world.