When the Losers of the History of Science Fight Back

How a French zoologist tried to take down Darwinism

Hello internet friends! I am using this newsletter as a space to share the interesting things I encounter in my research which don’t quite fit in any of my projects and would otherwise sit collecting digital dust in a poorly organised file on my computer. To kick things off, here is the story of how a French zoologist tried (and failed) to take down Darwinism. Don’t forget to share and subscribe as they say.

At the end of a career of almost six decades, in the first pages of the last book he ever published, French zoologist Pierre-Paul Grassé compared Darwinism to an “incurable disease.” He wrote:

Everyone should know by now that Darwinism is an ideological system that does not account for evolution in the slightest.

Such a statement would perhaps not have been out of place in the decades around 1900, when Darwin’s theory of natural selection was still being widely contested. But Grassé wrote these words in 1980, when Darwinism had become the dominant view among biologists.

Indeed, between the 1930s and 1950s, a group of biologists combined the findings of genetics and the theory of natural selection. This ambitious enterprise, named “Modern Synthesis” was the result of the collective works of life scientists from different backgrounds (including genetics, embryology, ecology, zoology, palaeontology, and botany). The group, though dominated by English-speaking scientists, was fairly international. For the remainder of the 20th Century, this new Darwinism established itself as the main framework for thinking about organisms and their history.

But France did not get the Darwinism memo. The first French chair of genetics was created in 1945 – decidedly late in comparison to other Western countries — and the chair of “Evolution of Organised Beings” at the Sorbonne was held by a long line of anti-Darwinian biologists from its creation in 1888 until 1967, when Grassé retired.

At a time when Darwinism was the dominant view in the scientific world, the vehemently anti-Darwinian Grassé was far from being marginalised in his home country. Au contraire, he was one of the most respected and institutionally powerful scientists of his generation. In fact, in the second half of the 20th century, he was among the main gatekeepers of his discipline, wielding so much institutional power that his monumental Traité de Zoologie, published in 48 volumes over the course of several decades, was, until relatively recently, an absolute reference for French biology students who simply called it “le Grassé.”

Historian Jean Gayon cites a sense of “injured national pride” as one of the reasons for the widespread dismissal of Darwinism by French life scientists, from the publication of the Origin until the late 20th century. In 1959, while over two thousand international guests gathered in Chicago to celebrate the centenary of the Darwinian revolution, in France, the Revue d’histoire des sciences dedicated an issue to their own evolutionary hero Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck. In his contribution, Grassé promised to “restore the truth”: the theory of evolution was not a British discovery, it was French. Lamarck was the true father of evolution, not Darwin! Two years later, one of Grassé’s colleagues, Albert Vandel declared:

Evolutionism would have known a better development if, fifty years after [the publication of Lamarck’s Philosophie Zoologique], Darwin hadn’t driven it down an unfortunate route where it almost got stuck.

Grassé rejected the Neo-Darwinian idea that the accumulation of accidental genetic mutations, in conjunction with natural selection, could give rise to complex structures such as the eye or the human brain. There was, according to him, an element of directionality in evolution. Such intricate organs could not be the result of pure chance. He also tied his anti-Darwinism into his reactionary politics. He believed that “ideologies” like Darwinism, in which chance prevailed over deeper meaning, had made Western society deeply sick. Other causes of this sickness included television, women using contraceptives, existentialism, and a basic loss of catholic values.

For all his criticism of Darwinism, Grassé never provided a robust counter-explanation for evolution that could replace natural selection. So, to establish himself as legitimate alternative, he found himself resorting to different strategies, some more historical than biological. Without making any attempt to disguise the nationalistic character of his narratives, he insisted that evolutionism was a proud French tradition linked to French thinkers like philosopher Henri Bergson, Jesuit palaeontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and of course Lamarck. The rival Anglo-American tradition, to which the Modern Synthesis belonged, had on the other hand given rise to considerably fewer geniuses.

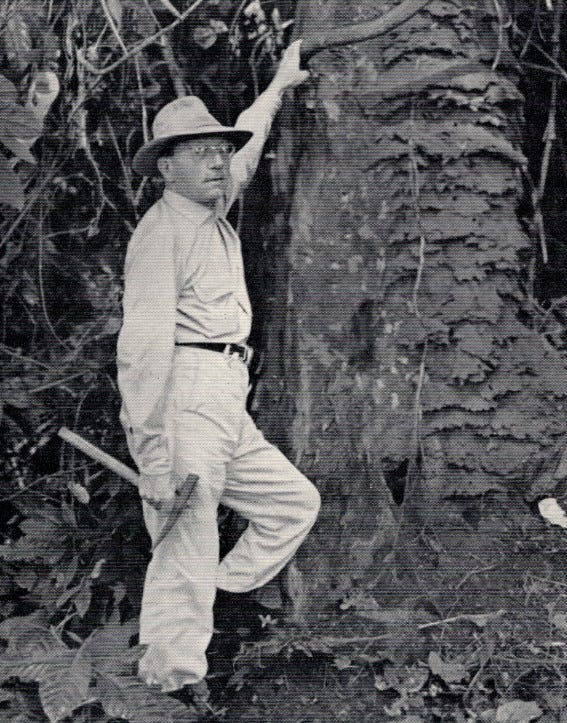

As the representative of the “intellectually superior” French tradition, Grassé saw himself as a naturaliste. Like Buffon, Cuvier, and Lamarck before him, he prided himself in possessing encyclopaedic knowledge about all aspects of the natural world and mastering numerous scientific disciplines. The Neo-Darwinians of the Modern Synthesis, on the other hand, glorified a different kind of scientist, one who had emerged at the end of the 19th century: the specialist. According to Grassé, the Darwinian scientist lacked the intellectual depth that only a genius having devoted their life to the study of nature could possess. In 1968, he wrote:

The foundations of science were built by lone men. A Lamarck […] contributed more to the progress of science than any industrious but unimaginative army.

By ignoring the legacy of great, French, natural historians of the past, the architects of the Modern Synthesis were, he believed, unable to produce a true synthesis; instead they proposed a superficial aggregate of isolated and badly coordinated, specialized knowledge. To the figure of the Darwinian specialist, Grassé opposed the Lamarckian naturalist, a human encyclopedia, whose life was devoted to the production of a “true” synthesis upon which future naturalists could build.

Grassé’s attacks never elicited a response. The “unimaginative” Darwinian scientists were well assured that their work would allow them to carry biology into the future. They saw no need to engage in a debate they had already won.

Everyone is familiar with the truism (likely falsely) attributed to Winston Churchill according to which “history is written by the victors.” Here we have an interesting case of a historical “loser” constructing a narrative to write himself into the history of science.

Grassé’s Lamarckism, and his resistance against the notion that there was ever anything like a “Darwinian Revolution,” was part of a strategy to establish himself as the representative of a legitimate tradition of evolutionary thought. When scientific arguments failed him, he resorted to historical narratives in which he was the hero of his own Lamarckian story. Grassé believed evolutionary biology was still awaiting its revolutionary moment and that it was up to him to set the record straight.

If you want to learn more about Grassé and weird French science, I recently published a chapter on this very subject in a recent volume Imagining the Darwinian Revolution (edited by Ian Hesketh) I will happily send you a pdf of my chapter. If you need any of the references I can also provide them via email.

Thanks for this, Emily. It reminds me of some of Stephan Jay Gould's essays challenging us to question some of the cultural baggage that went along with Darwin and the Modern Synthesis. I had no idea that point of view was so entrenched in French science though!

It's such a pity. Man wasted his whole career.